Fabric of our lives. I wish I kept my mother’s trunk. It was filled with fabrics and needlework supplies. I was thinking about that old trunk as I prepared to interview Dindga McCannon, multimedia artist and Harlem resident. Dindga is the guiding force behind a group art show Harlem Memorabilia: Reflections in Fiber, set for an opening reception on Thursday, March 14, 5-7:30pm at Interchurch Center’s Treasure Room Gallery; and an art talk & walk, Tuesday, March 19, 1pm. RSVP 212-459-1854.

This amazing show, March 4— March 26, moved me to reflect. It took me over a decade before I would sell my mother’s home and get rid of things after her transition. After speaking with Dindga about Women’s History Month, inheriting old stuff and creating art from it, I began to recall memories. On the last day at mother’s brownstone, I left her trunk and two upright pianos. I was told: “No one wants that “old junk trunk”! Relatives said that they would take the pianos if I paid for tuning and moving. “Oh, Really?”

I refused to dump mother’s possessions at the curb. But, I could not keep them. I was in a dilemma. I justified leaving the old trunk safely in the house. I thought that maybe because the new owners were distant relatives, that they might find some use for that old stuff. My inner artist had long been submerged by grief on that last day at mother’s house. Today, I would have easily found a way to keep everything.

My mother told me that she inherited that old, heavy, wooden trunk from her mother. When my maternal Chinese-Caribbean grandmother arrived in Harlem from Trinidad, she found it on a sidewalk. She painted it with colorful flowers and it moved into her life. That trunk moved with her every time she moved—to various Harlem apartments, down to the Bowery, to 14th street, Chinatown, and eventually to our house on President Street in Brooklyn. The trunk, now painted grey, was last kept in our basement. It was intermingled with my mother’s and grandmother’s things—vintage fabric and tapestries, sewing notions like zippers, snaps, hooks, buttons, beads and fibers including yarn, threads, twines, ribbons, sequins, lace, fringe, trimmings, tassels, and crochet, knitting, embroidery and art supplies. There were also patterns, old greeting cards, and how-to booklets. My maternal elders were talented craftswomen and they made everything with their hands—upholstery, apparel, costumes, rugs, curtains, quilts, pillowcases and other domestic items.

As a pre-teen, I used to spend hours going through that trunk when it was set upstairs in our dining room. My mother had told me once that there was money buried in it because Grandma always hid her money. So, dollar bills were always at the back of my mind as I sifted through it. That old trunk was sometimes used as side seating dressed with a home-made skirt and a rectangle cushion or a sideboard covered with a custom tablecloth.

I did not realize it then, but that trunk was filled with the fabric of our family’s life. The trunk contents told stories about how our blended West Indian and American Deep Southern traditions were literally intertwined and threaded together. I learned to sew, knit, crochet, embroider, braid, weave, and dream from my maternal elders. Mother and grandma both had sewing rooms filled to the rafters with their needlework supplies. That trunk was for leftovers and stray items as far as they were concerned.

Mother, Carmen Wong and grandma, Violet Chan Keong, did teach me a lot despite me being left-handed. But my maternal Aunt Sybil Romain was the virtuoso. She was the undisputed Queen Bee, a maestro! In another time, she would have been the first Vera Wang. She ran her own successful, exclusive bridal salon on Jamaica Avenue, Queens that catered to Caribbean Chinese, Indian, Latina and Afro-Caribbean clients. Mum, as we all called her, was my mentor and Godmother. She was known for her high standards and exacting temperament. She was more than a seamstress. She designed, created and produced. A perfectionist, she would tear out your stitch if it was crooked, undo a hem if it was uneven and scrap your fabric if she thought it was wrong for the design. She would yell too if you did not follow instructions. My cousin Sandy and I had our own sewing projects and special assignments from Mum. Some of these included simple repairs, button replacement, zippers and assisting her with her numerous client projects. “What are we, slaves?” we mumbled to ourselves.

We were a human assembly line in her sewing room. We had to pin the patterns to fabric—very carefully! Sometimes, she created the patterns drawn on paper bags based on magazine photos. The next phase was to carefully cut out the garment pieces. When all the labeled pieces were cut and laid out, they looked like a puzzle. It always seemed a miracle that all the pieces fit together. We learned how to curate too, as Mum’s clients loved details like trimmings, lace, ribbons, beading, and lush linings. We tagged behind her from one end of the city to the other searching fabric stores and digging in remnant bins. All the while, Mum was constantly instructing us on how to examine fabrics for things like quality, texture and defects especially on silk, chiffon, taffeta, cotton, rayon, wools, blends. We had to measure, match colors, lines, adjust beading and myriad details for her huge multicultural weddings. Everything had to be “just right.”

Our “home-training” taught us so many things—about thrift, pride, dignity and survival. Those simple activities were also life lessons on entrepreneurship, diligence, excellence, focus, practice, patience, creativity, meditation, prayer, self-respect and self-expression. Because of this background, I have never been bored a day in my life.

So, I am grateful to Dindga for helping me remember my girlhood sewing lessons in honor of Women’s History Month. Thanks to her guidance as a master teacher, multimedia artist and author, and the efforts of a talented group of artists, women’s traditional fiber arts are the centerpiece of a Women’s History Month exhibit.

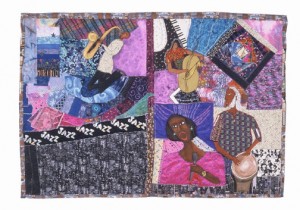

The show will feature a stunning collection of art quilts and hand-made cloth books. Congratulations to the featured artists: Angela Loftin-Blake, Phyllis Bowdwin, Jackie Burgess, Shirley Burton Cox, Lisa Curran, Valerie Deas, Shimoda, Izola Emanuel, Laura Gadson, Nancy Ivy, Shani Jamila, Arlene “Kweli” Jones, Nora Lee, Barbara Mims, Tanya Montgut, Rita Strictland, Olga Torrey and Dindga McCannon.

Didga McCannon’s comments: “Since I am now the eldest in my family, I taught my daughter and granddaughter about continuing our needlework traditions. At 9- years old, my granddaughter announced that she is an artist. I am so proud of her. It is important for us to respect and nurture our girl’s artistic dreams and to let them know that their ideas are not crazy. From the beginning of time, women artists had limited chances of developing and rare encouragement. But some of us managed to break through. I was blessed with great mentors and was featured early in my career at the Cinque Gallery and other places.”

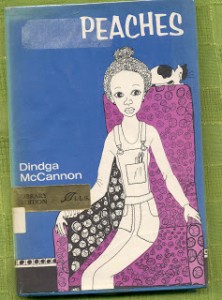

“I work intuitively fusing my art training with the traditional women’s needlework taught to me by my mother, Lottie K. Porter and grandmother Hattie Kilgro—sewing, beading, embroidery and quilting into what is now known as artquilts,” said the author of Peaches, a book about the adventures of a young girl who wants to be an artist, that she authored and illustrated, as a teenager.

McCannon, 65, who has a strong sense of family and community believes that one of the best things we can do for Women’s History Month is to nurture girl artists and teach them traditional women’s skills. “My early training came from my mother and grandmother. It is our duty to pass down our traditions. They need these skills to help them relax, counter peer pressure and computer buzz. Some girls are taught skills but not about art. But traditional training is an important first step towards artistry.”

When asked if she considered herself a feminist, Dindga said: “I don’t know if I would call myself a feminist. But I have long been included in feminist literature because I started a Black women’s art collective in the 70s and advocate for women.”

McCannon, who studied at the Arts Students’ League and City University of New York, attended Harlem’s PS 157 at 127th Street & St. Nicholas, now an apartment building; and Junior High School 143 at 129th Street @ Amsterdam Avenue, the setting of her first book Peaches. McCannon still believes the mantra: “A woman’s work is never done.” Happy Women’s History Month!